I’ve been contemplating tragedies recently. Just to be clear, when I say “tragedies” I’m thinking particularly of literary ones. There are most definitely plenty of tragedies happening in our world currently, not to mention travesties1, which tend to lead to tragedies. But I’m focusing on literary tragedies—how they’re similar, how they differ, and how they help me understand real life.

To start off, let me define what I mean by a “literary tragedy.” According to our massive Webster’s Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language a tragedy is “1) a dramatic composition, often in verse, dealing with a serious or somber theme, typically that of a great person destined through a flaw in character or conflict with some overpowering force, as face or society, to downfall or destruction.” If you’re interested in how a general real-life tragedy might be defined, you can go to entry #6 under “tragedy” which states, “a lamentable, dreadful, or fatal event or affair; calamity; disaster.” As I said, I’m focusing on the first definition, particularly as it relates to Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Macbeth which I’ve read with my son this year, and the musical Hadestown which retells the Greek tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice (Note: there will be minor spoilers, but “tragedy” sort of gives that away to begin with!) It’s so interesting to me how each story pulls out a different element of tragedy.

For example, in Hamlet, the Prince of Denmark is a young man of integrity who is beset with depression and doubt throughout the play. He wants to act and to avenge his father’s murder, but he keeps testing things and questioning his motives and those of others. He is conflicted about the words of his father’s ghost, the actions of his guilty uncle, the changeable love of Ophelia. Half the time he doesn’t step forward and take action, and so misses opportunities to resolve the matter. Other times he acts impetuously, and as a result acts wrongly. All of this leads to the death of many, including Hamlet. It is a classic story of a great person who falls because of a flaw in character.

Then there’s Macbeth who starts out as a great hero and an honorable man. When he gets a taste for ambition and power, though, things go south quickly. The pages of the Scottish play are drenched in blood as Macbeth tries to hack his way to stability and sanity. His method obviously doesn’t accomplish his goal, and things are only realigned when Macbeth is killed. One could argue that the witches in the play are the instigators of everything, but the “overpowering force” is Macbeth’s own ambition. It’s devastating to see.

Finally, there’s Hadestown, which I was able to see last weekend with my kids and my nephew, and which laid the foundation for this contemplation. If you don’t know this musical, look up the soundtrack at least, or try to see it. It’s amazing. As I mentioned, it’s a retelling of Orpheus and Eurydice, set in a fantastical New Orleans-ish place with a 1930s Depression-era vibe. It follows the original myth closely, but adds layers of theme and story that enrich and deepen the tale. In the original story the tragedy is outside of Orpheus—fate and the restrictions set by Hades, the god of the underworld, are the reasons for the tragedy, and Orpheus’ failure to rescue his Eurydice from death is gut-wrenching because it is cruel chance that causes it. The musical adds character layers both to Orpheus and Eurydice, and these augment strengths and flaws that make the characters relatable, but they don’t cause the final tragedy. That blow is outside of their control—when Orpheus steps out of Hades and turns in joy to be reunited with Eurydice, only to discover she hasn’t gotten out yet, he loses her forever—it’s an awful blow even when we know it’s coming.

Each of these tragedies hit me in different ways. I ache for Hamlet throughout his story—I know what it’s like to be hampered by indecision—the desire to do what is right, and yet the fear of hurting someone unnecessarily, or of being rejected. In Macbeth, my anger grows throughout the play as innocent people are slaughtered because of one man (and his wife’s) desire for power. I am angry and I’m horrified as things grow more and more grim, and I’m relieved when Macbeth is finally taken down. It’s a tragic fall, but in it I see good and right judgment—justice overcomes an awful wrong. Finally there’s Orpheus where I see his love for Eurydice and his desire to bring beauty and harmony to the world—he succeeds in so many ways, and in the musical Hadestown he brings restoration and wholeness to unexpected places. All throughout the story I am hoping he’ll succeed in saving Eurydice and I’m crushed when he fails.

Yet I know he couldn’t succeed. No matter how many times we retell his tale, it will end the same way. Angelina Stanford of House of Humane Letters talks about how the Greek myths with their demigods and failed heroes are precursors to the one story where the incarnate God dies, travels into hell, and succeeds in breaking it wide open, coming back to life and making a way for others to follow. As I watched Orpheus sing to the people of Hadestown and bring light into the darkness, I remembered Dante’s Inferno where Dante sees the destruction of places in Hell left by Christ’s upheaval when he entered it after death and rescued his own. In contrast, Orpheus tried and failed to bring out Eurydice and the others. In the musical, the narrator Hermes says we will tell the story again and again, hoping the ending might be different this time. I knew this story would always end the same, but my heart soared, because I know the ending where things did end differently, and tragedy was turned by eucatastrophe2.

So yes, literary tragedies are on my mind. I can’t help but connect them to real life as I watch this sad world of ours struggle to figure things out, and leaders push and shove, and people desperately try to save themselves and others and often fail. It’s easy to get lost in the tragedies—to only see the sorrow and hopelessness. But then I see the story of Orpheus, and as I watch him trudging and trudging up out of the darkness of Hades, my eyes well with tears because I know that though he’s going to make it, Eurydice won’t. At the same time, I know that I’m crying for joy, because I have a savior who did succeed, and the tragedy is ultimately a comedy.

1 According to Webster’s definition: 1) a literary or artistic burlesque of a serious work or subject, characterized by grotesque or ludicrous incongruity of style, treatment or subject matter; 3) any grotesque or debased likeness or imitation

2 From Wikipedia: A eucatastrophe is a sudden turn of events in a story which ensures that the protagonist does not meet some terrible, impending, and plausible and probable doom. The concept was created by the philologist and fantasy author J. R. R. Tolkien in his essay "On Fairy-Stories", based on a 1939 lecture. The term has since been taken up by other authors, and by scholars.

Art for the week

Tragedy or not? The past few years my daughter Evie has submitted art work to our local art museum’s student invitational. Last year we were really excited when her painting won third place in that category. She had a vision for this year’s piece, and hoped to do work that was better than last year’s. I found out today that her piece didn’t win anything this year, and I dreaded telling Ev. Imagine my delight and relief when she took it in stride. “That’s okay,” she said. “I like it.”

I like it, too, so here it is for you to enjoy. If you happen to be in Longview over the next month or so, you can go to the Longview Art Museum where all the student artwork is displayed. Jon even submitted a photo with some other students from our homeschool coop—I’ll put that in my next letter.

Five more days to back this lovely book!

I am so excited about this fabulous anthology of poetry for kids that Bandersnatch Books is hoping to put out in the world! Every time I turn around I find out another friend has poems that will be featured in it—and they are such good writers! If you’ve never backed a Kickstarter, basically it means you are helping make this project a reality—and you’ll get your own book through it. You can find out more about it here. This project will run until March 11.

Rachel Donahue and Carolyn Givens talk more about the book in this episode of The Banderpod—you can hear a couple of the poems at the end!

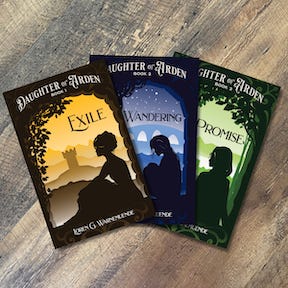

Check out Daughter of Arden at Bandersnatchbooks.com, along with other great titles.

You can find links to more of my writing at A Shaft of Sun Through the Rain and my old blog, Willing, Wanting, Waiting.

Why do I like a good tragedy? At the end there may not be a wedding and a feast, but there is justice that leads to hope. Even though Hamlet ends in a bloodbath, there is hope that the new ruler will bring peace to Elsinore, there is hope that the Montagues and Capulets have learned their lesson, there is hope that the Donuts and the Chowders are free of the evil in their midst. And as we look forward to the Resurrection, yes and Amen! We get it all: the justice, the wedding, and the feast! Thank you, Loren!

I also love reading tragedies. This post came around at just the right time, too, since I've just finished reading Le Morte d'Arthur - another tragic tale, though not a play. Thank you for sharing your thoughts.

(And Evie's art piece is gorgeous! I especially like the curling leaves. I'm glad she loves it even though the judges didn't.)